By: Stan Bevers, KRIRM Practitioner in Ranch Economics

Feature appeared in the KRIRM Fall 2020 Newsletter

Horses play a large role on today’s commercial cattle ranches. From carrying the ranch brand at playdays to carrying ranch hands gathering cattle, they are a source of pride and an important ranch tool. On some ranches, they provide a valuable revenue stream, while on other ranches they are simply a necessary expense. Ranch owners, general managers and cowboys have long debated the financial role that these horses play. Is the remuda a profit center or a cost center? This case study demonstrates a process for determining the financial role of the remuda on a commercial cow-calf ranch.

Is the Remuda a Profit Center or a Cost Center? For accounting and analysis, most ranch activities can be isolated into profit centers, cost centers, or support centers. The use of support centers isolates the fixed costs of the ranch into four groups: general and administrative, labor and management, machinery and equipment, and interest costs. By this definition, the remuda is not a support center.

A cost center accumulates expenses (and some revenues) for specific activities on the ranch, but are not associated with the support centers. These activities are deemed critical to fulfilling the goals of the ranch, can be measured, and should be monitored. The accumulated expenses of each cost center are transferred to profit centers or to the balance sheet as investments. Specific examples are hay production for a ranch where most of the hay is fed to the cattle. There can be some revenue associated with a cost center such as selling a small amount of hay, but the primary purpose is to feed cattle, so the accumulated costs are then transferred to the appropriate profit centers (cow-calf profit center). Other cost centers are investments that are transferred to the balance sheet at the end of the year. For example, raised replacement heifers are critical to the operation, can be measured, and their costs should be monitored. These costs represent an investment in a replacement heifer asset that is then transferred to the balance sheet. Using either of these examples, a remuda could be viewed as a cost center.

A profit center reflects the revenue and expenses associated with the products sold at the end of the production cycle. Sales from profit centers are used to pay their own direct expenses, as well as those allocated from support centers and transferred from cost centers. Weaned calves, stocker cattle, and harvested wheat are all examples of ranch profit centers. In this case, the remuda could be considered a profit center.

The goals of ranch ownership should determine whether the remuda is a cost center or a profit center. If the primary purpose of the remuda is to supply ranch horses to employees, then remuda is a cost center. Production inventories and financial transactions should be tracked, and its total costs should be minimized. The total net expense will be transferred to a profit center such as the cow-calf and stocker profit centers.

If the goal of the remuda is to generate a positive net income that contributes to overall ranch net income, then it is a profit center. While minimizing expenses is probably warranted, focus is placed on creating desirable colts, aged geldings or mares that can be marketed to cover direct expenses as well as a portion of support center associated cost center expense. In this case study, the remuda will be treated as a profit center.

Accounting for the Ranch Remuda as a Profit Center. Most ranch financial accounting is targeted to minimizing tax liabilities. Ranchers need to be reminded occasionally that financial record keeping and accounting are done for more reasons than determining and minimizing these liabilities. Managerial accounting can be used to analyze any activity’s financial efficiency or contribution to overall ranch income. A case study of a commercial ranch that has a remuda defined as a profit center has been created to demonstrate this concept. This case study is a near-world situation with three goals for the ranch remuda: 1) Sell a portion of the raised inventory for a profit; 2) Raise mares and purchase mares and/or stallions to sustain the breeding remuda; and 3) Supply saddle horses for the cowboys to utilize in cattle operations. The purpose of this case is to determine the financial role of the remuda to the overall ranch.

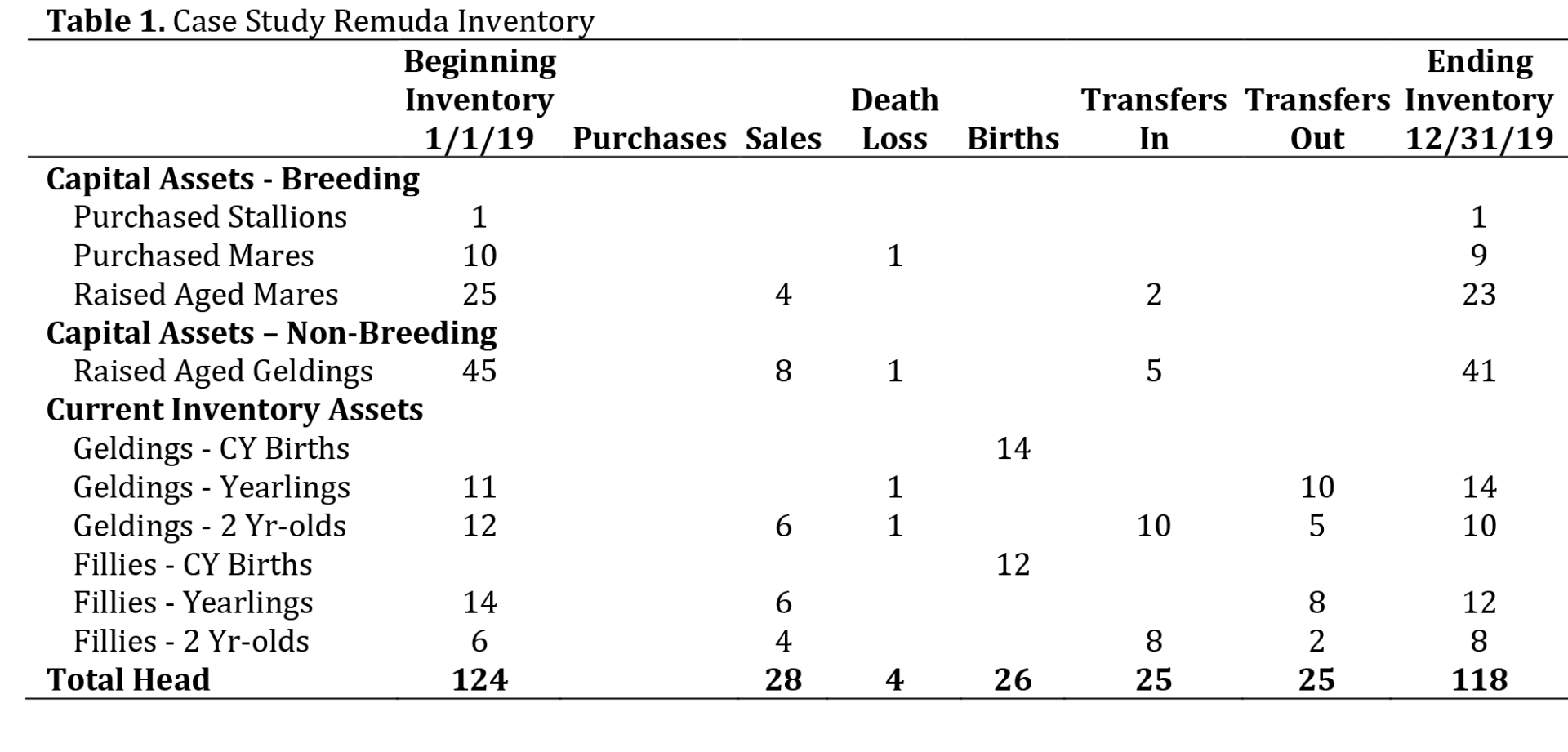

The Remuda Inventory. Any good management system includes inventory of the livestock. Table 1 details the remuda inventory for one year. The horses are broken into three types. The first are Capital Assets – Breeding. The beginning inventory includes one purchased stallion, ten purchased mares, and 25 raised mares. These are all balance sheet, depreciable assets (although using tax accounting would not include depreciation of the raised mares). However, one of the monitoring points for the remuda is to determine cost to produce a raised aged mare and/or gelding. The second group is Capital Assets – Nonbreeding, and includes raised, aged geldings. The table shows four raised mares and eight raised geldings were sold in 2019, a purchased mare and a raised gelding died, and two raised mares and five raised geldings were transferred in as capital assets at the end of 2019. Each of these items are important because the sales are not simply revenue. The ranch sold capital assets that have been depreciated in prior years and as such, a capital gain or loss must be determined. The death losses are a capital loss if the horses had a net book value remaining on the depreciation schedule. Horses transferred in were placed in service on the ranch and added to the depreciation schedule at the value of the accumulated expenses incurred to create them (their cost basis).

The Current Inventory Assets are raised colts less than three years of age. Geldings and fillies are further broken down into current year births, yearlings and two-year-olds. The ranch sold six two-year-old geldings, six yearling fillies, and four two-year fillies. These sales are simply (current) inventory revenue. At the end of the year, colts on inventory are transferred to the next age group. Once any remaining two-year-olds reach the end of the year, they are transferred out of their group and moved to either the raised aged mares or geldings (placed in service). This entire reconciled inventory is imperative to calculating the profit center’s contribution to the ranch net income.

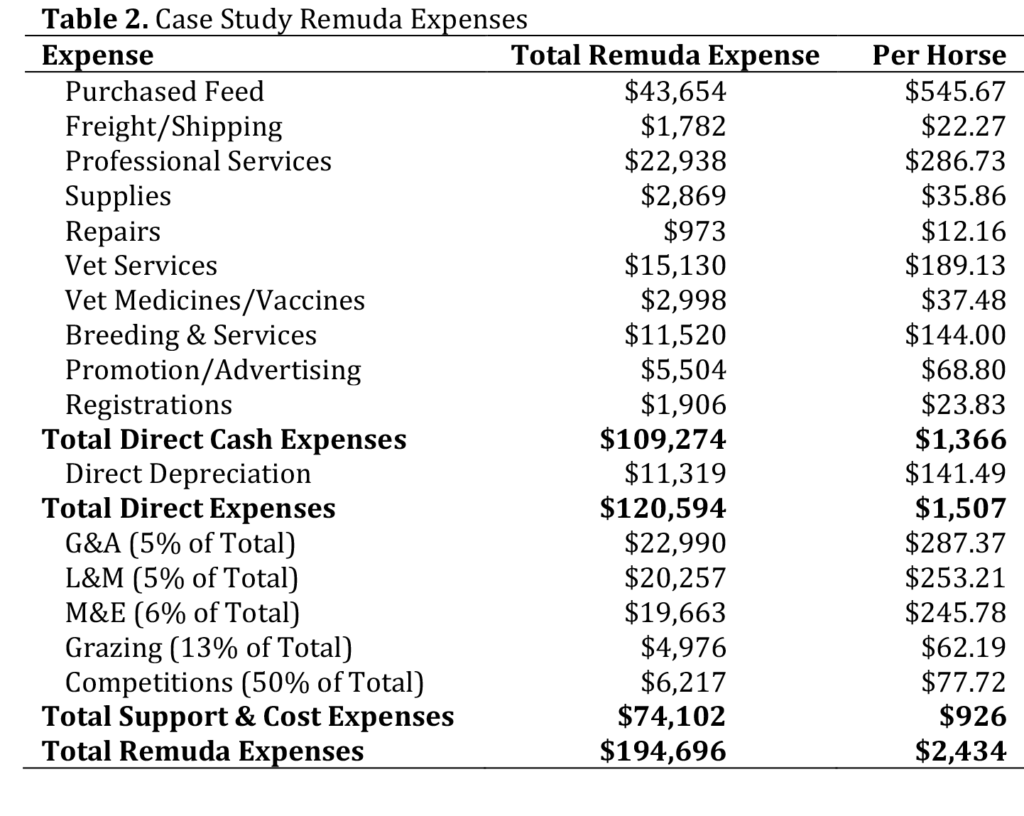

Remuda Expenses. Because the remuda is defined as a profit center it has its own direct expenses and a portion of expenses from other cost and support centers of the ranch. Table 2 shows the detail of these expenses. The per head costs are based on aged horse inventory at the beginning of the year. Direct cash expense is $109,274, and the largest direct cash expenses are purchased feed, veterinary expenses, and professional services. The remuda has direct (non-cash) depreciation expense of $11,319 on purchased mares and stallions and infrastructure specifically for the remuda. Total direct expenses are $120,594. The remuda must cover its share of other ranch costs. Percentages of three support centers (general and administrative, labor and management, and machinery and equipment) and two cost centers (grazing and competitions) are allocated to the remuda. The grazing cost center includes a portion of expenses intended to improve ranch grazing, while competitions includes ranch rodeo or show entry fees and travel expenses. The total allocation from cost and support centers is $74,102, and combined direct and allocated remuda expenses are $194,696. In this case study, it costs $2,434 to maintain one horse asset on the ranch annually.

The Remuda’s Sale of Aged Horses and Death Loss. Some aged horses are sold each year, primarily trained geldings (8 head) and raised mares (4). These inventory changes can be seen in Table 1. From a net income standpoint, the ranch sold depreciable assets so a capital gain or loss must be calculated. To calculate capital gains (losses), the sales value is reduced by the net book value (NBV) of the asset. NBV is the original purchase price (or cost basis) minus the accumulated depreciation since the asset was placed in service. These were raised mares, so the ranch doesn’t have an original purchase price, but used the accumulated expense of raising the mares as the cost basis. The NBV for these horses’ totals $1,796, resulting in a capital gain of $15,004 for the sale of raised mares. Likewise, the ranch sold eight raised aged geldings for $36,000; their NBV was $7,457, resulting in a capital gain of $28,543 for the sale of aged geldings. The ranch also recorded the death of two horses, a purchased mare and a raised gelding. The mare had been depreciated out (NBV equals zero) while the NBV of the gelding was $922. Since there was no revenue, this results in a capital loss of the same amount.

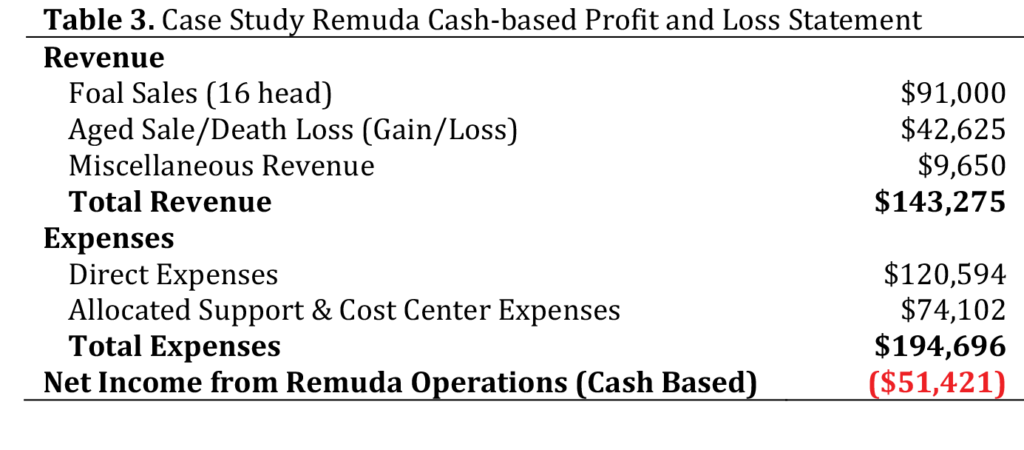

Total sales and death loss of aged inventory assets resulted in a total capital gain of $42,625. Capital gain income offsets some of the $194,696 remuda expense described above. Breakeven is calculated by taking the total expense minus secondary revenues like capital gains. Breakeven expenses for this remuda are $152,071 ($194,696 minus $42,625).

The Remuda’s Cash-based Profit and Loss (P&L) Statement. Based on inventory (Table 1), the ranch also sold 16 yearling and two-year-old colts. These sales are different from the sales of the aged mares and aged geldings in that these have never been “placed in service” as a depreciable asset. As such, these are simply sales of current inventory. The two death losses of gelding colts are simply inventory loss. Current inventory foal sales, combined with the aged horse sales and miscellaneous revenue from competitions result in the revenue side of the cash-based profit and loss summary shown in Table 3. The cash-based profit and loss statement shows a negative contribution to the overall ranch net income, but this isn’t the end of the story.

Allocating the Ranch Remuda Costs to Other Centers and Balance Sheet. Recall that the remuda has three goals that affect expenses allocation from the remuda to other centers and assets. Goal 1 causes a portion of the expenses to stay with the remuda to offset the revenue from the foals. Goal 2 forces some of the expenses to move to the balance sheet to create depreciable assets (i.e., raised mares), while goal 3 causes some expense allocation to the cow-calf profit center. Thus, we allocate the remuda expenses to those ranch activities that receive benefit from the remuda, in the same way that other ranch activities allocated portions of their expense to the remuda. Recall that the remuda breakeven expenses was $152,071 and these expenses must be allocated. Management determined that cow-calf allocation would be 50% of remuda expenses. We can never know what the exact allocation should be, but through trial and error, an allocation percentage can become focused. In this case study, 50% is $76,035 that will be allocated to the cow-calf profit center. This results in a charge of $22 per cow over 3,500 cows for the use of the remuda’s ranch horses. The remaining 50% of expense stays with the remuda and must be allocated across all groups of horses, the capital assets and the current assets.

To complete the accrual-based P&L, we must also incorporate the inventory changes of the current asset inventories. At the end of the previous year, production costs invested in the growing of yearling and 2-year-old colts were moved to the balance sheet as a current asset of investment in growing livestock. There were 43 colts on inventory and their accumulated expenses ($73,267) moved to the current year P&L statement, matching the inventory in Table 1. Throughout the current year these colts were trained, sold, a few died, and more were born, and they all became one year older. At the end of the year, 44 colts were in each of these groups and were added to the current inventory balance sheet. Further, 2 aged mares and 5 aged geldings were added to the capital assets as depreciable assets. The accumulated expenses of these 51 horses totaled $70,747. This total is broken down as 12 yearling fillies ($8,062), 8 two-year-old fillies ($17,915), 14 yearling geldings ($9,935), 10 two-year-old geldings ($23,499), two aged mares with an accumulated cost of $3,135 ($1,568 per head) and five aged geldings were added with an accumulated cost of $8,201 (1,640 per head).

Did the remuda contribute positively to the overall ranch net income? Yes, the remuda contributed $22,095 to net income. Table 3 summarizes the accrual-based P&L statement for the case study remuda. Horse sales and miscellaneous revenue totaled $143,275. The total adjusted remuda expenses were $118,661, while the remuda inventory change resulted in an increase of expenses of $2,520. The net income from remuda operations on an accrual basis is $22,095. The ranch remuda sold a portion of their inventory (foals and aged horses), added raised, aged mares to sustain the remuda, and added raised, aged geldings to their inventory for the cowboys to use in cattle operation.

Key performance indicators for the remuda include: 1) the cost to maintain a ranch horse ($2,434); 2) the cost of weaning a filly ($672) and gelding ($710); and 3) the accumulated cost of a 2-year-old filly ($2,239) and a 2-year-old gelding ($2,350). Furthermore, the remuda created and supplied breeding mares to sustain the band at a cost of $1,640 per mare, and finally, the remuda supplied aged geldings to the ranch’s cattle operation for $1,568, certainly cheaper than the price of most aged (and trained) geldings.

In summary, the remuda can play an important role in commercial cattle operations. As ranch margins tighten, every support, cost and profit center should be evaluated to determine operational efficiency within the ranch and identify opportunities for improvement. To complete this type of evaluation, financial transactions must be allocated to the proper centers. Inventories of assets and production must be maintained and reconciled for accurate evaluation. Accrual-based accounting systems more accurately describe the financial influence of the ranch remuda on your operation.

View story in the fall 2020 newsletter here.

Download a pdf of the newsletter here.