By Rick Machen, PhD

The US beef industry is experiencing record high prices for calves, feeder and fed cattle. Cow prices are rising rapidly and expected to surpass 2014-15 replacement female prices.

La Niña weather patterns are shifting to El Niño. Great Plains soil moisture conditions are improving; the current U.S. Drought Monitor map has improved appreciably (except Kansas and eastern Nebraska) since January. Widespread rainfall and rising prices are reason for excitement in the beef industry.

Recall the 2014-15 scenario wherein consumer demand for beef was strong, beef supply had decreased, and record prices resulted. Optimistic cattlemen paid high prices for replacement females (ex. $4,250 per head for open two-year-old crossbred heifers). Almost a decade later, a retrospective look indicates those record high replacement female prices had a lingering effect on weaned calf unit cost of production.

Unit cost of production is calculated by dividing total annual cow maintenance cost by average weaning weight adjusted for weaning rate. (Unlike breakeven cost, the calculation does not include secondary income (ex. revenue from open replacement females, market cow and bull sales)). Supplemental nutrition, labor, and depreciation are typically among the top five contributors to annual cow cost. Supplemental nutrition is influenced by weather and stocking rate, labor is usually a fixed cost. Depreciation (a non-cash cost) can be influenced by management actions/decisions.

Two variables determine depreciation: cow cost and salvage value. Annual per head depreciation is determined by dividing the cow cost – salvage value difference by years of useful life. Most managers adopt the IRS allowable five-year useful life. Some argue that the useful life denominator should be longer (i.e. 7 years); note that depreciation (numerator) is not influenced by useful life.

Results of a KRIRM study considering the relationship between cow longevity and cow/calf enterprise economic performance indicate that, using an average 87% weaning rate and an aggressive once open culling practice, average cow age was 6.76 years. Consequently, a five-year depreciation schedule for commercial cows seems appropriate.

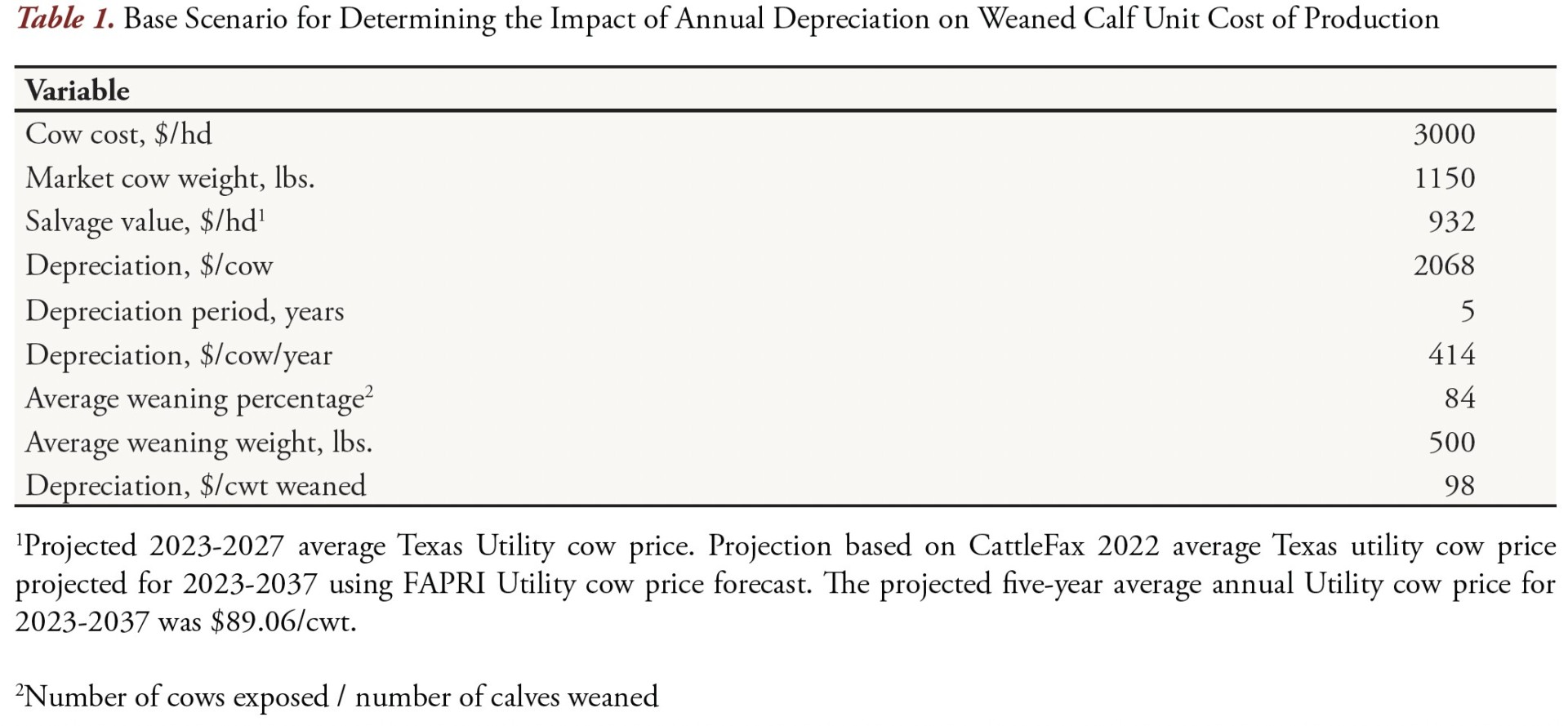

Annual depreciation is often quantified as dollars per cow, and since it is a non-cash cost, it tends to get lost in the numbers. Perhaps a more resonating approach is to quantify the impact of cow purchase price (and the concomitant depreciation) on weaned calf unit cost of production. The base scenario for such a comparison is described in Table 1.

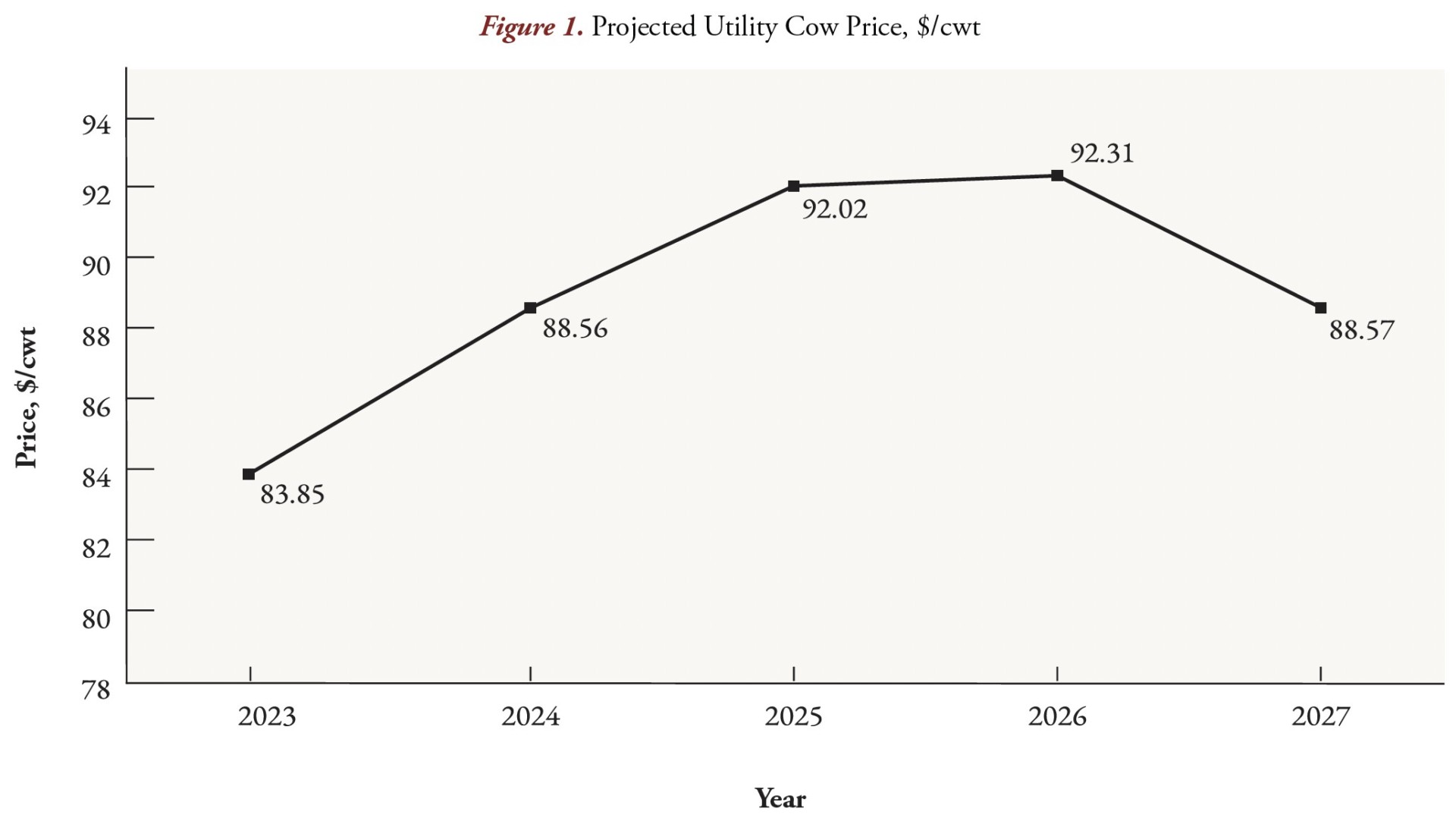

Assumptions for the two depreciation variables are merely a starting place. For the base scenario, a cow purchase price of $3,000 per head seems reasonable given current market conditions. Since depreciation is calculated over a five-year useful life, a five-year average utility cow salvage value of $932 per head (1150 lbs., $89.06/cwt) was determined as described in the Table 1 footnote. Projected annual average utility cow prices for 2023-2027 are shown in Figure 1. According to CattleFax data, using a 2022 Texas Canner/Cutter cow annual average price ($71/cwt) would have lowered the base price for projections by $6/cwt.

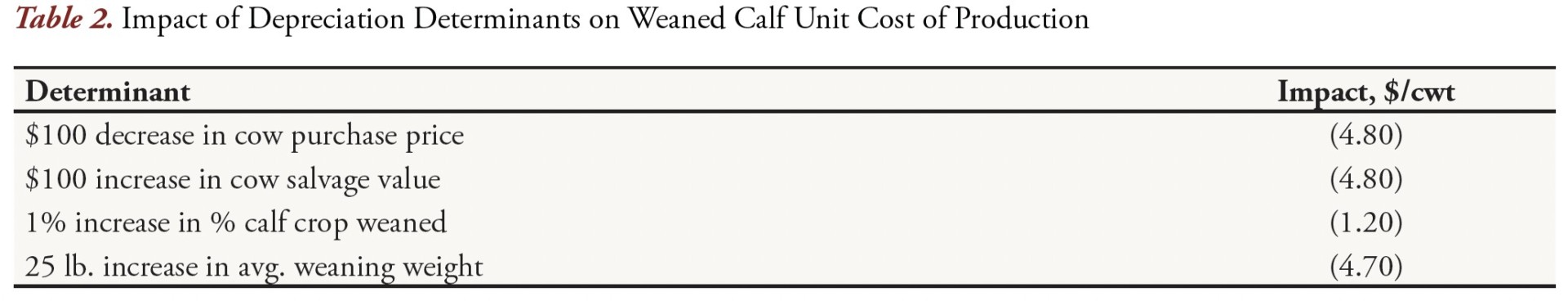

The influence of four primary variables involved in calculating depreciation’s contribution to weaned calf unit cost of production is shown in Table 2. Note the impact of cow depreciation: $98/cwt of calf weaned for five years. Decreasing purchase cost or increasing salvage by $100/head had the same $4.80/cwt impact. A 25 lb. increase in average weaning weight had a similar $4.70/cwt impact. A 1% increase in calf crop weaned reduced depreciation per cwt of weaned calf by $1.20. Note the combined impact of the four changes is $15/cwt ($84/cwt of calf weaned). Recall this appreciable addition to weaned calf unit cost of production is for a five-year period.

The disparity between market price for replacement quality heifers and the book value of raised heifer calves will encourage the retention and development of replacement females. Larger cow/calf operations that need several hundred (or more) replacement females annually will continue to retain and develop and thereby enjoy an economy of scale advantage. Ranches that choose to purchase replacement females usually assume greater depreciation cost per cow.

Though not included as a variable in the analysis, cow longevity has an obvious impact as well. Cows that remain productive beyond their removal from the depreciation schedule turn the depreciation expense to a ‘depreciation credit’. Productive cows remaining in the herd after weaning a fifth calf do not incur depreciation expense and therefore wean calves with a lower unit cost of production. Likewise, long productive cows reduce the number of heifers kept for replacement or the number of cows purchased in a high-priced market.

In market conditions like those described in the opening paragraph, it is easy to get caught up in the “never going to be another bad day” mindset. The scenario developed here likely does not mirror that of any reader, nor is the intent to dampen the current beef industry enthusiasm. Rather, the intent is to encourage ranch managers to make decisions in the long-term best interest of the cow/calf business by remembering to consider the long-term implications of cow purchase price.

As featured in our Fall 2023 Newsletter, view more here.