by Clay Mathis, PhD

Droughts are inevitable and each one demands a management response. Protecting drought-stressed natural resources (soil and forages) for the long-term and sustaining the ranch business isn’t easy. Since each drought is different and may occur at different stages of the cattle cycle, the best management actions vary as well. The good news in 2022 is weaned calf prices have been on the rise and are forecasted to be 20 to 30% higher over the next three years. Nonetheless, drought has plagued Texas and the majority of western and plains states in 2022. The shortage of precipitation and grazable forage this year has resulted in drought-forced liquidation for many. Making the decision to liquidate even a portion of the herd is painful. Part of the struggle is knowing that after it rains and the pastures turn green, restocking will be expensive. Restocking with higher cost females will increase cow depreciation in the years that follow. Granted, most producers implement a teared approach to selling females, and often also incorporate a degree of drought feeding and even early weaning to balance forage supply and demand. These tactical efforts are rightly intended to prevent overutilization of forage and postpone liquidation in hopes that rain will come before significant liquidation is required.

Drought-Induced Liquidation’s True Cost

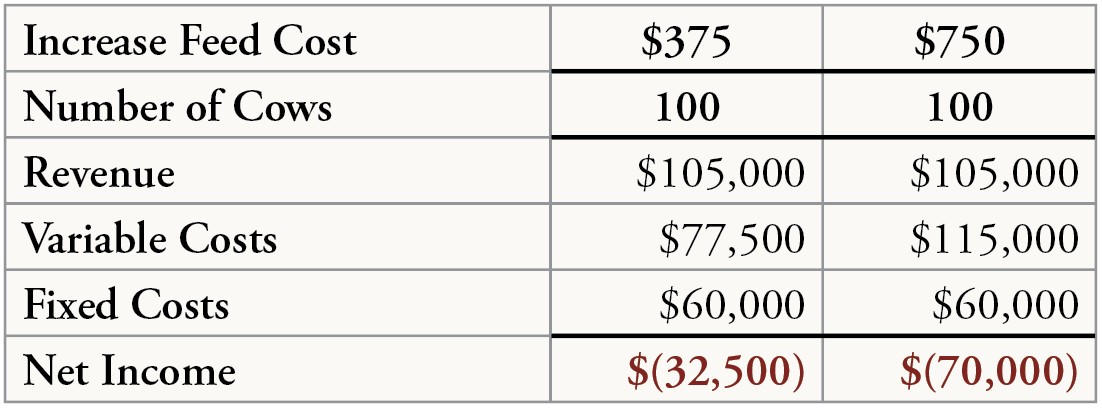

This is tricky to estimate because we don’t know when a drought will end. Every operation is different, so let’s consider an example ranch (Table 1) and the financial implication of destocking. This example assumes that 40% of the total $1,000 annual cow costs are variable and 60% are fixed. The fully stocked, 100-cow enterprise profits $5,000; a net income of $50/cow. If the 100-cow herd is reduced by 33% to balance forage supply and demand, then net loss equals $16,450. Notice that revenue declines by $2.6 for every $1 decline in variable expenses; fixed costs remain unchanged. The same principles hold true with enterprise losses of $37,900 associated with 66% herd reduction; $42,900 less net income than when fully stocked.

Unfortunately, that is not the end of the story. Liquidation of cattle in a suppressed market only to buy back similar class cattle in an inflated green grass market must also be considered. To fully recover the herd, the example scenario assumes the same class of cows liquidated in 2022 are purchased post-drought for $500 more than liquidation value. This price difference is very conservative considering the cow price increase following the drought of last decade. With a $500/cow buyback adjustment to net income, the impact of destocking by 33 and 66 percent relative to the fully stocked scenario is a devastating $-37,950 and $-75,900, respectively. Since fixed costs remain unchanged regardless of cow inventory, the decision to retain or sell cows is based on: 1) how cost-effectively additional variable cost (i.e., feed) avoids liquidation, and 2) access to capital to purchase additional feed/hay.

Is Avoiding Liquidation Affordable?

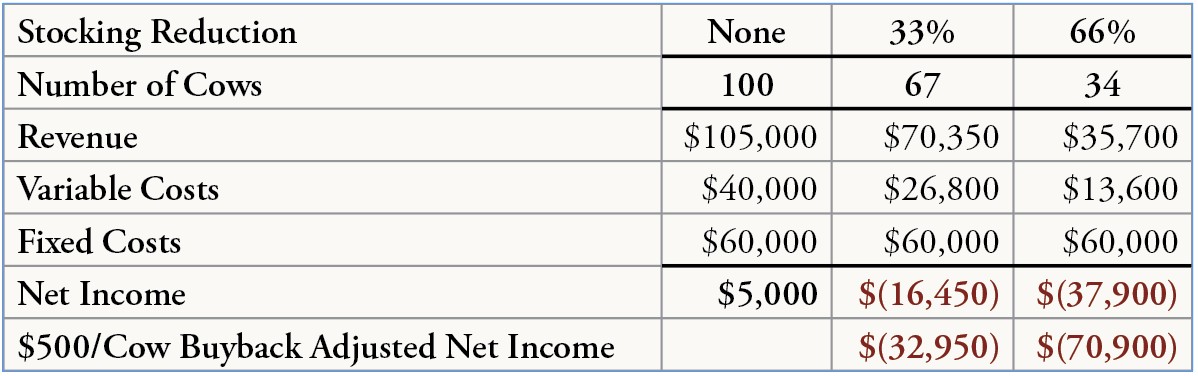

Predicting the blessing of drought-breaking moisture is impossible, therefore increasing costs to avoid liquidation is a risk-inherent investment to buy time. Table 2 utilizes the same 100-cow herd example. Increasing feed cost per cow by $375 or $750 to postpone liquidation aligns closely with net income in the 33 and 66 percent destocking scenarios. Bottom line is the revenue from cows is needed to cover fixed costs, and revenue declines 2.6 times faster than variable costs when cows are liquidated. If capital reserves are available, the tolerable liquidation-avoiding variable cost investment is often greater than initially perceived.

Rangeland stewardship should remain the number one priority in drought response, so a multifaceted approach that includes mild liquidation, supplementation, and early weaning may be the best option. However, it is helpful to understand that: 1) the fixed cost will remain regardless of how many calves are sold, and; 2) maintaining financial reserves or other access to capital facilitates consideration of a significant increase in variable cost to avoid excessive herd liquidation.

This example highlights the financial aspects of drought and hopefully assists management with making best decisions in a tough situation. Accurate assessment of production costs is foundational to decision making. Fixed costs are independent of cow inventory; hence the reason drought-induced herd liquidation can financially devastate the ranch. If feedstuffs or capital resources are available, consider retaining and feeding cows through a relatively short-term drought and being positioned to capitalize on projected improvements in calf prices. Should drought persist longer than the one-year horizon in this example, appreciate the additional risk. Ranchers are eternal optimists who eagerly anticipate the next rain. Hopefully it comes soon.

Table 1. Financial implication of 33 or 66 percent drought-induced cow liquidation, including net income adjustment for post-drought restocking with higher priced cows.

Table 2. Financial implications of increasing variable cost (nutrition) by $375 or $750 per cow to postpone drought-induced liquidation.